The term “restorative practices” is tossed around a lot these days, and this multipart series can help clarify what it looks like on the ground.

‘Who Has Been Hurt?’

Mariana Souto-Manning, the president of the Erikson Institute, has developed programs and taught courses in areas such as teacher education, early-childhood education, and inclusive and bilingual education. Souto-Manning has (co-)authored 10 books, dozens of book chapters, and over 85 peer-reviewed articles:

Restorative justice practices attend to victims’ needs—for information, truth-telling, empowerment, restitution—and offenders’ obligations, departing from focusing on who broke the rules and what punishments they deserve (criminal justice). Restorative justice recognizes that offenders need to assume responsibilities, change their actions, and become fully contributing members of communities.

For this to happen, offenders need accountability, addressing harms, encouraging empathy, and fostering responsibility. They need to be encouraged to undergo and experience personal transformation—healing from harms that contributed to their actions, receiving mental health treatment, etc. These transformations enhance their self-esteem, identity, and competencies. They take responsibility for the community they harmed and their welfare, attending to their concerns and seeking opportunities to build community and develop answerability.

In schools, restorative justice practices may mean that instead of defaulting to time-outs, traffic lights, and suspensions (which disproportionately affect Black students), asking: Who has been hurt? What are their needs? And then embrace the obligation—collectively—to right wrongs, moving toward a more just future. Rooted in respect and the understanding that we are all interconnected, restorative justice practices require naming who is at stake and deciding on the process whereby stakeholders put things right, addressing both harms and causes of offenses.

Restorative justice cultivates and sustains school communities where students feel belonging, are valued, and feel heard and understood; this is reflected in their academic success. But this does not happen without respect for all, focusing on harms and needs, and inclusive and collaborative processes, addressing obligations and involving multiple stakeholders.

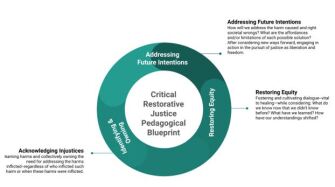

Although there are multiple ways and models for restorative justice practices, they have three common actions: acknowledging the wrongs and injustices, restoring equity, and addressing future intentions. The pedagogical blueprint I developed (below) accommodates these actions.

Image by Mariana Souto-Manning

Here is a short example from Jessica Martell’s 2nd grade classroom in a public school in New York City, organized according to restorative justice actions:

ACKNOWLEDGING INJUSTICES

On the morning after the police officer responsible for Eric Garner’s death was acquitted, a free local newspaper distributed at New York City’s subway stations featured a “NO CHARGES” front cover. It was not uncommon for Jessica’s students to bring a copy of this newspaper to school, highlighting stories and headlines. That morning, as soon as they saw Jessica, one student held the paper up and said, “No charges? Not guilty. Can you believe it?” Another asked: “Do Black lives really matter?” “Yes, Black lives matter!” affirmed an Asian American student, chanting: “Black lives matter. No justice, no peace,” while pumping his right fist, as he had done in the #BlackLivesMatter marches the night before alongside his mother. Yet, most the class remained silent until Ana, a fair-skinned Latina girl said, “All Lives Matter.” Many students nodded.

RESTORING EQUITY

Jessica called the entire class to the rug area for a meeting. She wrote down “Black Lives Matter” and “All Lives Matter” on the easel, inviting the children to read the statements and discuss them with their “turn-and-talk” partners. Jessica then asked them to explain what each statement meant. Ana expressed that since Jessica had said that as human beings, we are all unique and special, that “all lives matter.” Rashod responded, “We know that all lives should matter, but the only people being killed are people who look like me, not you. So, we know that your life matters, but does mine?” Rashod continued, “If Black lives mattered, then there wouldn’t be so many Black people being killed by the police. I’m scared that the police might shoot me one day, or my dad. I’m afraid I’m gonna get shot and die. Are you?” Students sat silently.

ADDRESSING FUTURE INTENTIONS

Offering a compass to future intentions, Ana looked at Rashod and responded, “You’re right.” As students named and unpacked society’s racial injustices via critical dialogue, they collectively addressed their future intentions-—building a more racially just community in their classroom and committing to ensure that Black Lives Matter each and every day.

Restorative justice requires shifting philosophy, engaging in training and ongoing support for the wider school community, including teachers, administrators, support staff, families, and caregivers. It promotes a culture of respect, empathy, and answerability. It offers a framework for addressing learning that promotes healing, understanding, and positive relationships.

Building Relationships

Renee Jones is the 2023 Nebraska Teacher of the Year. She teaches AVID and 9th grade English at Lincoln High School. Follow her on Twitter @ReneeJonesTeach:

It is commonly acknowledged that relationships are the key component of academic success. Restorative practices place relationships and connections as the foundation of all skills and academic gains, rather than as supplemental to the learning objectives. Restorative practices focus on building inclusive spaces and respectful relationships in order to effectively work with the students we are serving.

Restorative practices, in my classroom, means building a classroom community, one that is rooted in collaborative norms and commitments that were made together, as a class, rather than for a class. This community establishes acceptable behavior, increasing accountability and buy-in to our curriculum.

Restorative practices look like providing intentional opportunities to engage in an interactive dialogue that creates critical thinking while increasing executive-functioning skills.

Restorative practices look like practicing skills that our foundational to being engaged in the community we’ve built. One of my favorite practices includes integrating connection circles, a formal conversation where class members stand in a circle and speak one at a time while holding a talking piece, in an effort to reflect and contribute to higher-level thinking questions. This discussion welcomes each student to engage authentically in a discussion about themselves, connecting with the curriculum, and taking a risk that includes elevating their voice into the discussion.

Restorative practices is a shift in mindset and can be woven into every lesson and every student interaction we engage in. Restorative practices cultivate students, and teachers, to work together to acknowledge differences and to have a reflective conversation when conflict arises. Restorative practices encourage individual conversations that repair harm and reintegrate individuals, providing opportunities for growth and redos rather than a penal archaic punishment that often focuses on shame. Restorative practices provides an opportunity to learn from the harm done, by acknowledging our individual role and making intentional steps to repair and move on.

Restorative practices provide opportunities for the student to focus on building themselves as a whole individual, understanding that failure is part of the learning process, and that relationships are the foundation of personal and academic growth.

‘School Culture Is Positively Impacted’

George Farmer, Ed.D., is a passionate administrator dedicated to growing teachers, developing students, and empowering parents. He is the author of the blog FarmerandtheBell, which provides solutions to current educational challenges:

Restorative practices have gained support in recent years as an attempt to close the disproportionality gap of exclusionary practices from schools for Black students. Suspensions became the primary means by which students (predominantly Black) were excluded from school. Instead of correcting students’ behavior, out-of-school suspensions increased, resulting in students missing academics, thus increasing educational gaps.

Exclusionary practices isolate students from their peers and learning environment. Exclusionary practices involve taking students out of the educational setting for a period and then putting the student back into the same environment often without guidance or support, to avoid repeating the actions that led to their exclusion. When students are placed back into the same environment without proper support, the same behavior is repeated, leading to more exclusionary practices.

Restorative practices explore holding students accountable by restoring or repairing harm done to relationships before exclusionary measures. A school that builds its culture on restorative practices is a school where students are reflective and held accountable by addressing the root of student behavior instead of the manifestation.

There are several methods of restorative practices in schools. Restorative circles are a common tool in restorative schools. A restorative circle is a safe space where every student has the opportunity to share their perspective and work toward a resolution. Every participant has a chance to speak, and only the person with the talking stick is permitted to speak. Restorative circles are a great way to model for students how to resolve conflict peacefully.

Respect agreements are another helpful tool in schools that utilize restorative practices. Respect agreements are a contract created by students and teachers to establish a classroom code and serve as guidance for classroom culture. The agreement is signed by everyone and becomes a point of reference for any violations.

When schools use restorative practices, school culture is positively impacted as students share in the community and are held accountable for their actions. Restorative practices decrease exclusionary practices that fail to restore relationships and reinforce positive behaviors.

‘Suspension Creates a Harmful Path’

Michael Gaskell is a veteran principal in New Jersey. He has written books (Microstrategy Magic, Leading Schools Through Trauma, and Radical Principals) and presented on disrupting inequity, at numerous national conferences including Learning and the Brain and FETC:

The Restorative Service Program (RSP) engages faculty one-on-one with a child to talk about constructive ways to deal with issues that cause them to get in trouble. Teachers begin by building relationships as they are intentionally unfamiliar with the student. This prevents accountability bias, such as a teacher who grades a student. The adult serves exclusively in a mentoring role that is nonpunitive. The relationship is fostered as the child sees the adult in the hall and elsewhere, and positive interactions flourish. Best of all, colleagues see this teacher engaging constructively with at-risk children.

RSP targets student misbehavior in a nonpunitive way. Students are guided to more constructive behaviors that enable them to focus on the future and the positive, rather than the past and punishment. Let us examine the process for RSP.

- A student exhibits misbehavior. This may result in a bullying investigation, due to disrespect toward authority or other inappropriate action that is referred to the school administration.

- The administrator issues the necessary (if applicable) disciplinary consequences and separately, recommends a nonpunitive RSP.

- A faculty member who does not teach the identified student is assigned to meet with the child during the available/duty period.

- The faculty member is given a summary of the infraction and uses the sample guide and one of the corresponding activities with the student.

- The teacher files the reflection documents the student worked on in an archive.

- Monthly meetings are held to review these documentswith administration and to make recommended revisions.

Suspension creates a harmful path for at-risk children, leading to further discipline and reinforcing the disaffected nature of such children. Reverse this by showing a caring adult offers an alternative. This kind of approach has a longer term, better sustained impact on both children and school culture. We see nothing less than a win-win from adopting it.

Several RSP-trained teachers had this to say about their experience with this different approach:

a) This initiative has given students the unique opportunity to reflect on their actions, empowering them to identify how they can positively modify their behavior in the future for a better outcome.

b) I meet kids I would not know otherwise, and afterward, they have a connection with an adult, possibly for the first time in school that is not biased by grades or other areas they struggle in. They continue to seek me out as a guide, a coach. It is powerful!

c) Before we did restorative service, I didn’t know who they were and I just saw them in the hall wreaking havoc. I admittedly made assumptions about them. Now, I’m building relationships and see them not as child in the hall and instead someone I can help adjust and succeed. The connection is powerful, and the neutral ground we play on allows the opportunity and choice to excel where they previously didn’t have this choice.

Here is what some of the kids had to say about RSP as an alternative to discipline:

i. Getting to talk to the teacher who I don’t know and just wants to help me makes me feel like I have someone who really cares. I didn’t think anybody cared before and I’m not always good, but now, I want to try because I know someone expects me to.

ii. Being in this program was fun. I got to talk to him about my side, and hear what I can do next time, instead of keep getting lectured about what I did wrong.

iii. It’s nice to have an adult to talk to that doesn’t judge me. She just wanted to help. It made me think about how to fix my problems.

It is important to recognize how valuable this resource program is, how it offers at-risk children a chance. Still better, it offers the entire school an opportunity for a culture shift. Creating a respectful, tolerant culture creates a safe space for children to learn, to make errors, and to recover with support.

Thanks to Mariana, Renee, George, and Michael for contributing their thoughts.

The question of the week is:

What are restorative practices, and what do they look like in schools?

In Part One, Marie Moreno, Chandra Shaw, Angela M. Ward, and David Upegui shared their experiences.

In Part Two, Ivette Stern, Caroline Selby, Gholdy Muhammad, Nadine Ebri, and Tatiana Chaterji discussed their experiences.

In Part Three, Ann H. Lê, Sebrina Lindsay-Law, Douglas Fisher, and Nancy Frey wrote their answers.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at lferlazzo@epe.org. When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo.

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email. And if you missed any of the highlights from the first 12 years of this blog, you can see a categorized list here.